“If a kid doesn’t pass organic chemistry he probably shouldn’t become a doctor. DO the parents actually think lowering standards will help us compete around the world?” =Katty Kay on Real Time, Friday night.

Just when you thought sanity might be returning to academia after the pandemic lockdowns, we learned an esteemed Organic Chemistry prof was dismissed from NYU because students complained his "course was too difficult". The little dweezils (82 of them in a class of 305 evidently signed a petition “expressing concern” about the effectiveness of Prof. Jones’s teaching. Large numbers of students were receiving low scores on exams, and some had withdrawn from the course. Since they'd all planned on a medical school background this was all too much, as it scuttered their precious plans.

Give me a break, do.

Maybe, just maybe, they shouldn't have been taking organic chemistry in the first place, and hey, maybe medical school should not have been their career preference if they couldn't handle it. Maybe, in fact, they weren't cut out to be doctors anyway. Maybe their better choice might have been orderlies. Just sayin'.

But this type of entitled brat behavior is about as sensible as a 2nd year physics student bellyaching that quantum mechanics is "too hard". Well, excuse me, maestro, WTF did you expect? It's quantum mechanics, not basket weaving or speech!

All this was learned last week when The New York Times reported on the firing of N.Y.U. professor, Maitland Jones Jr. after the student blowback. Prompting Bill Maher, in one riff last Friday night, to question whether we need to describe these complaining students as 'snowflakes' or morons for not grasping that organic chem is a difficult course by nature. If you're not prepared you shouldn't be taking it, any more than an unprepared physics student should be taking quantum mechanics.

Why the big deal anyway? In my Calculus General Physics class – which I

taught at a Maryland college in 1992-93,

I gave Ds and Fs to no fewer than 8 of 15 students. Why? Because they refused to do the work,

they wanted to “skate”. I saw no need to reward lax achievement, despite giving them all kinds of outs - including extended time to turn in labs, as well as special tutorials after classes, and even relevant formula pages for exams.

Tressie McMillan Cottom in

another NY Times piece nailed it when she wrote:

“Depending

on your perspective, this is a story about snowflakes run amok, the decline of

Western education or the intolerance of hypercompetitive academics.”

How about the first two in tandem? Let’s also point out – as Dr. Cottom notes, Jones taught organic chemistry as a contingent (or adjunct) faculty member at a private university. The majority of higher education professors are now contingent, meaning that they do not get the protections of tenure. This is also the position I held at the Maryland college. So both he and I were expendable. (He was likely doing it as a ‘gig’ job to help support his retirement). Both Prof. Jones and myself were relegated to this contract lecture limbo because colleges, universities have become too cheap to hire full time staff. They want to cut corners. See Physics Today, November 2018, page 22.

As Dr. Cottom also notes, such contract (adjunct) professors are very vulnerable. When teaching contracts are fungible, administrators rely more heavily on student evaluations than they do peer evaluations. These are the lazy modes of assessing professor quality, but beyond the maturity level of 95% of college students. They simply lack the frontal lobe development and emotional maturity to give objective assessments, which is why I've always been against them. See e.g.

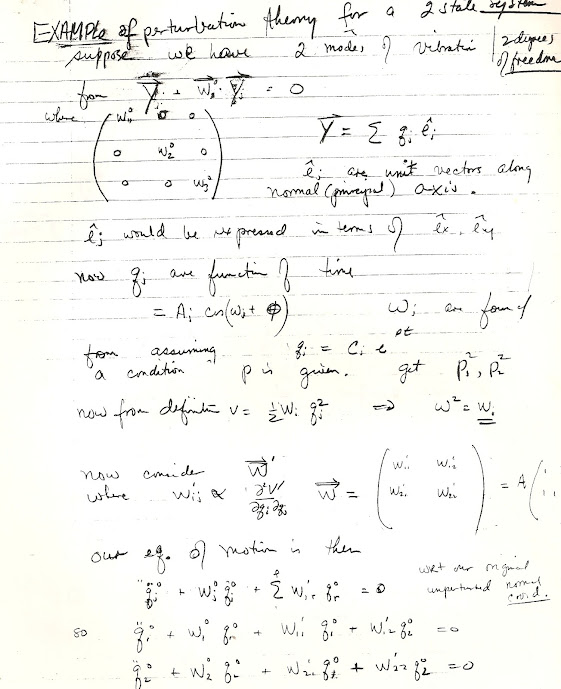

But the same thing used to be said in the 60s about classical mechanics to "weed out" all the would -be rocket engineers and space hot shots who wanted to bandwagon their way into Physics or Engineering after Sputnik. But they had to know it would not be a cakewalk if they picked up even one textbook beforehand. Below a page from my classical mechanics handout notes from way back then:

So then as now, too bad Bud (or Betty), but maybe you ought to have chosen something more in line with your actual aptitudes.

Some writers have insisted that Jones’s teaching struggles are common "when generations collide in the classroom". But I don't buy that malarkey. It's just a cop out. As Katty Kay intimated on Real Time, do Gen Z students really expect easier courses to plot their path to med school and become doctors? Then maybe they shouldn't become doctors.

But as Ms. Cottom points out, it isn’t just about generational differences, it is about a course like organic chemistry, which is, in part, designed to filter out students unsuited to rigorous pre-med curriculums. So what's wrong with that? All training for higher end, status careers or positions have their own "filters". You think all those who want to be Navy Seals make it through? 'B-but that's different, that's military!"

No, it isn't different. A medical doctor can determine a patient's life or death depending on whether s/he fouls up in a surgery, or prescribes the wrong med. A clown for a doctor can make things go south in a hurry. So we need certain courses as barriers to weed out the losers, and lazy skaters.

The real bottom line is that those parents whose charges attend an expensive private university do not expect them to bail out or to fail out. They spent too much already on this kid's education and no hot shot professor is gonna wreck the kid's chances. This is in light of the fact the estimated total cost of attendance for an on- or off-campus student attending N.Y.U. over the 2022-23 school year is $83,250. Administrators at such tuition-dependent universities have a lot of incentives to make sure that their students do not fail. They are now selling a product after all and they need more consumers.

According to another NY Times contributor, a Prof. Jessica Calarrco from Indiana University, the kids are really being bodacious and brave in their challenge to Prof. Jones. She writes.

"The N.Y.U. students’ willingness to challenge this kind of pedagogical gatekeeping is a sign of how power dynamics are shifting at colleges and universities in the United States. To some degree, that shift reflects a rising sense of entitlement on the part of students and their parents. But that’s not the only factor at play. Another is the increasing diversity of student bodies, which casts many higher education traditions in a new light. One of those traditions is the weed-out mentality. Courses that are meant to distinguish between serious and unserious students, it has become clear, often do a better job distinguishing between students who have ample resources and those who don’t."

Indeed, on perusing his Introduction I wondered how many of his students read the section on 'How To Study Organic Chemistry' - especially the part: 'Avoid Memorizing'. He writes that in the old days reliance on memory enabled many to get through but no longer. Now, "generalization and the understanding of principles" is critical. Then pointing out that those who memorize generally "do well early" - then crash in the middle of the first semester. They "run out of memory".

A perfect example of how that can occur appears in an end of chapter problem on p. 47, where we see one of the text's many inquiry problems:

In an alternative universe, the following restrictions on quantum numbers apply: n= 1,2, 3...

ℓ = n-1, n-2, n-3,....0

m ℓ = ℓ +1, ℓ …0, ....- ℓ- 1

s= + ½

Call the elements in this universe 1, 2, 3... and assume that Hand's rule and the Pauli Principle still apply.

a) For n= 1, 2 and 3 show what orbital subshells are available and label them s, p, d and f and so on.

b) How many electrons can be accommodated in the first three shells in this universe?

c)Provide electronic descriptions for elements 1 through 14 in this universe.

How many tried to rely on memory to do problems like the above and bombed out?

-------------

Finally, they seldom read exam questions properly before answering them, which was responsible for the majority of the low scores. Where Prof. Calarrco is more in line with judicious and fair solutions is when she writes:

"It also means providing resources to ensure that students aren’t facing pressure to try to overload on courses in order to graduate early and save on tuition, room and board. That they don’t have to juggle class work with working long hours for pay. And that they don’t have to circulate formal petitions to get the support and respect they deserve."

She also adds:

"Unfortunately, if not surprisingly, abundant evidence shows that universities are more responsive to requests from their highest-paying customers. With tuitions rising ever higher and government subsidies only a fraction of what they once were, universities are dependent on money from affluent families. That model pushes schools to cater to the demands of privileged students and their families, even though doing so increases inequalities."

But the good prof herself provides the optimal solution:

"Even in the absence of that kind of shift, though,

universities can do more to help students succeed in their classes, regardless

of the level of privilege they bring with them or the types of majors they

pursue. That means investing more in faculty hiring, to allow for smaller class

sizes, and in academic advisers and other student support staff members, who

are often deeply underpaid."

No comments:

Post a Comment