Spherical astronomy entails

the mastery of the basic relations for spherical trigonometry. This is merely an extension of

plane trig, but to the sort of angles (many > 90 degrees) one finds in astronomical applications, since distances, angles are of spherical measure (derived from spherical triangles.) A simple illustration of spherical

geometry is shown in Fig. 1. In the diagram, the angle Θ denotes the longitude

measured from some defined meridian on the sphere, while the angle φ denotes a

zenith distance, or the measured angle from an object to the zenith.

Fig.

2 shows a spherical right triangle from which a host of different angle

relationships can be obtained, which can then be used to find astronomical

measurements, etc.

Fig.3

shows a diagram of the celestial sphere, such as used in many practical

astronomy applications,

and some of the key angles with reference to a particular object (star)

referenced within a given coordinate system:

In some applications, the coordinate system may not need to be changed, but in

others it must - for example, when going from the coordinate system applied to

sky objects (Right Ascension, Declination) to the observer's own coordinates

(altitude, azimuth). In this way, coordinate transformations will also enter

and are straightforward to perform, for example via use of matrices.

We consider first a simple angle relation in Fig.

1, say to find the altitude, a. Then if we have the basic geometrical relationship:

a + φ = 90 degrees, then a = (90 - φ).

Let's now examine Fig. 2 and see what

spherical trig relationships we can infer.

Two of the key ones embody the law of

sines and law of cosines for spherical triangles, which are the analogs of the

law of sines and cosines in plane trig.

We have for the law of sines:

Sin A/ sin a = sin B/ sin b = sin C/ sin c

where A, B, C denote ANGLES and a,b,c denote measured arcs. (Note: we could

also have written these by flipping the numerators and denominators).

We have for the law of cosines:

cos a = cos b cos c + sin b sin c cos A

Where

a, b, c have the same meanings, and of course, we could write the same

relationship out for any included angle.

Now, we use Fig. 3, for a celestial

sphere application, in which we use the spherical trig relations to obtain an

astronomical measurement.

Using the angles shown in Fig. 3 each

of the angles for the law of cosines (given above) can be found. They are as

follows:

cos a = cos (90o - d)

where d = declination

cos b = cos (90 o - Lat)

where 'Lat' denotes the latitude. (Recall from Fig. 1 if φ is polar distance

(which can also be zenith distance) then φ = (90 - Lat))

cos c = cos z

where z here is the zenith distance.

sin b = sin (90 deg - Lat)

sin c = sin z

and finally,

cos A = cos A

Where A is the azimuth.

Example Problem:

Let's say we want to find the declination of the star if the observer's

latitude is 45 o N, the azimuth of the star is measured to be 60

o, and its zenith distance z = 30 o. Then one would solve for

cos a:

cos a = cos (90 o - d)=

cos (90 o - Lat) cos z + sin (90 o - Lat) sin z cos (A)

cos (90 o - d) = cos

(90 o - 45 o) cos 30 o

+ sin (90 o

- 45 o) sin 30 o cos 60 o

And:

cos (90 o - d) = cos (45 o) cos 30 o

+ sin (45 o)

sin 30 o cos 60 o

We know, or can use tables or calculator to find:

cos 45 o = Ö2 / 2

cos 30 o = Ö3/ 2

sin 45 o = Ö2/ 2

sin 30 o = ½

cos 60 o = ½

Then:

cos

(90 - d)= {(Ö2/ 2 )( Ö3/ 2)} + {Ö2/ 2} Ö (½) }

cos (90 - d)= Ö6/ 4 + Ö2/ 8 = {2Ö6 + Ö2}/ 8

cos (90 - d) = 0.789

arc cos (90 - d)= 37.o9

Then:

d = 90 o -

37. o 9 = 52. o 1

Or, in more technical terms:

d (star) = + 52.1

degrees

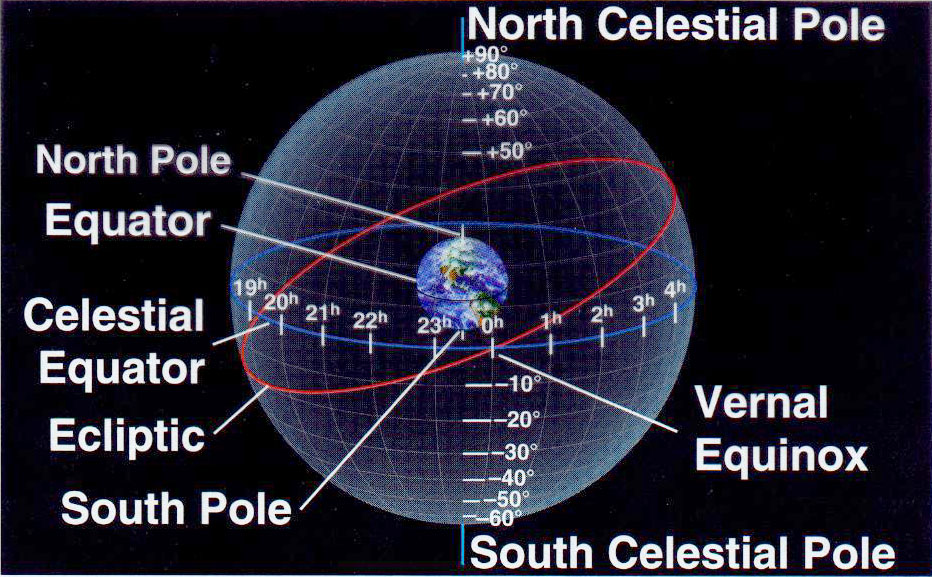

A more detailed image of the celestial sphere appears below with key aspects not found in the simpler version (Fig. 3):

In this detailed version we see the Earth's north pole is projected to the North Celestial Pole, the equator is projected to the celestial equator, and all latitude lines are projected to become declination lines, while longitude lines become Right Ascension lines. Thus, just as every geographical location on Earth has a latitude and longitude so also every sky location has a declination and Right Ascension. The "vernal equinox" position, for example, is at 0 degrees Declination and 0 hours RA. (The vernal equinox marks the first day of spring.)

The oblique red circle projected onto the celestial sphere defines the ecliptic or the projected (apparent) path of the Sun onto the celestial sphere through the year. If we follow the red circle - the ecliptic - UP from the vernal equinox we come to the northernmost point at +23.5 degrees declination and 6h RA. This coincides with the summer solstice - or when the Sun appears over that latitude on Earth. This marks the longest day of the year in the northern hemisphere

We are led then to consider how to compute star positions on this sphere (which had the designated coordinates of R.A. and declination) and also how to transform between coordinate systems, say between the horizon system and the celestial sphere (equatorial) system.

For example, the coordinate system depicted in the color graphic above - the equatorial system - is based on the projections of the Earth's own equator and N. and S. poles onto the sky sphere. The poles then become the North and South Celestial poles, and the equator becomes the celestial equator. If these poles are defined respectively at +90 degrees (NCP) and -90 degrees (SCP) and the celestial equator at 0 degrees, then a system of celestial latitude can be constructed.

Once the vernal equinox position is fixed at 0 hours R.A. then the celestial longitude emerges and spans 24 hours across the same celestial sphere. (Refer again to color graphic for direction of celestial longitude circles.) These can be used in conjunction with celestial latitude (declination) to locate any celestial object. It is then possible to make computations translating one system's coordinates to those of others (horizon, ecliptic etc.)

Example: φ = 51.5 degrees N, for London. Now, for the

December (winter) Solstice the Sun is directly over the Tropic of Capricorn

(φ = 23.5 S) therefore we do know its

declination is - 23.o5. We have then for the Sun's azimuth at sunrise in London on

Dec. 21:

cos (A) = sin (-23.o 5)/ cos (51.o 5)

which gives approximately, 130 o.

Where

is this on our directional reference circle for azimuth? We know that 180

degrees is due South so that this must be:

40 degrees SOUTH of due East. (90 o + 40 o = 130 o)

Now, on the longest day of the year (say June 21), the Sun is over the

Tropic of Cancer at 23.5 N latitude, so the Sun's declination is + 23. o

5 . Then the azimuth for that date is:

cos (A) = sin (23. o 5)/ cos (51. o5)

And A = 50 o

This puts the Sun's rising position

North of due E. or specifically 40 degrees North of due East.

Problem:

The

altitude of a star as it transits your meridian is found to be 45o

along a vertical circle at azimuth 180o, the south point. Find the declination of the star.

The basic principle involves relating the Cartesian coordinates (rectilinear) of a point on the celestial sphere (diagram) to the curvilinear coordinates measured in the primary and secondary reference planes. One has then, for example:

The basic principle involves relating the Cartesian coordinates (rectilinear) of a point on the celestial sphere (diagram) to the curvilinear coordinates measured in the primary and secondary reference planes. One has then, for example: