It seems almost like yesterday when we first heard of "exoplanets", large masses circling other suns outside our own solar system. That's until one realizes it was barely 26 1/2 years ago that Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz discovered the first such planet orbiting a sun-like star 50 light-years from Earth. That discovery—the first exoplanet confirmed around a sunlike star—recast the thinking about how planets form. It also so captivated the imagination that efforts to search for them soon became mainstream astronomy (see Physics Today, December 2019, page 17)

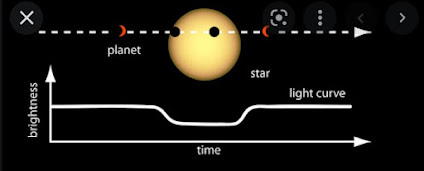

Barely ive years later, 34 exoplanets had been spotted around sunlike stars. Nearly all of them were observed by Doppler spectroscopy, which measures the periodic redshifts and blueshifts in a star’s wobble from an exoplanet’s gravitational tug. In 1999, Harvard University’s David Charbonneau debuted a complementary approach—the transit method, in which an observer looks for the brief dip in the brightness of a star when an exoplanet passes in front of it. The basic principle is highlighted in the diagram shown below.

What's truly mind -boggling is that these two methods have now been responsible for more than 4800 confirmed exoplanets. All of them are in the Milky Way and less than 3000 light-years from Earth. The vast majority were spotted by the Kepler and TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) space telescopes. We now recognize - thanks to these detectors - that planets are ubiquitous in the Milky Way, and astronomers estimate that one -third of all sunlike stars host planetary systems.

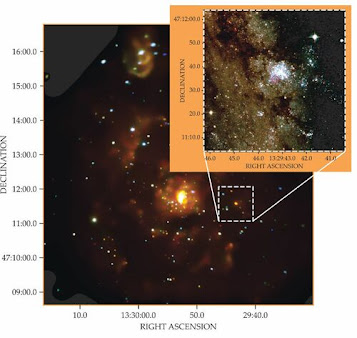

Enter now the potential for x-ray observatory detection of exoplanets in other galaxies. As "Exhibit A" a possible exoplanet orbiting one of the brightest x-ray binaries in Messier 51, the Whirlpool galaxy. To find it, the astronomers mined the vast archives of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, NASA’s flagship satellite x-ray telescope.

Composite images for object cited in text. Messier 51, known as the Whirlpool galaxy, reveals discrete x-ray light sources. The boxed region near a cluster of young stars contains an x-ray binary system. In the inset, the Hubble Space Telescope reveals an optically more crowded environment (the binary is circled in magenta).

Their automatic search of 2640 point sources in three galaxies yielded the features of an exoplanet transit in a 2012 light curve (see figure 2 below):

This curve (like the one shown earlier) yields the telltale feature of a planetary transit: the abrupt dip and subsequent rise in flux. Both consistent with a Saturn-sized planet.The researchers could not distinguish whether the compact, accreting star was a black hole or a neutron star, but in either case it was gravitationally bound to a blue supergiant companion whose luminosity and spectrum is that of a 20–30 solar mass star. Also, using Kepler’s laws, e.g.

They estimated its distance from the binary’s center of mass to be tens of astronomical units—about 45 AU multiplied by a scaling factor that depends on the binary’s mass. That inference puts the planet up to a quarter of a light-day from the stars—roughly equal to the distance between the Sun and the outer Kuiper belt in our own solar system—and its orbital period around 70 years.

Let's also note, however, that orbital period would be the longest ever found for a transiting exoplanet. And it likely puts the exoplanet’s confirmation—either from a repeat transit observation, Doppler spectroscopy, or both—out of reach for the current generation of astronomers.

This means that until such day we obtain an actual empirical confirmation we can only say this is a "possible" exoplanet in another galaxy. But look, this is not a one -off. Beyond the confirmed exoplanets in the Milky Way— 4878 as of December 2021—there are thousands of candidates that require more observations to be considered authentic. We could actually have 7 or 8 thousand possible exoplanets in our galaxy alone, but those additional ones all require confirmation. We can't just declare them exoplanets based on preliminary data.

See Also:

Physics Today, December 2019, page 17

And:

Physics Today, March 2019, page 24.

And:

No comments:

Post a Comment