First, climate change denier papers are generally dismissed precisely because they lack the basics of scientific authority - including: proper data selection, bias-free analysis, consistent interpretation of data, and appropriate mathematical techniques. Hence, their papers are tagged as the opposite of authoritative science.

Second, given all climate scientists must compete for scarce funding resources, they are not about to help a competitor - say set to publish a competing model or theory - merely because their research is in line with global warming /climate change.. Thus, if anything, peer review is likely to be even more rigorous than for deniers.

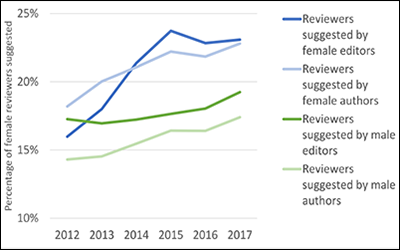

Having said that there are areas where the peer review process can definitely be improved, and not just in climate science but across the scientific publication spectrum.. One way would be in the removal of gender bias for selection of peer reviewers, which is now weighted heavily toward males. At the forefront is a recent study in Nature, showing that women were being used less as reviewers in nearly all age groups compared to expectations based on their higher success rates as authors and their distribution with age in the AGU membership. The AGU is the American Geophysical Union and comprises the largest professional organization of both climate scientists and space physics researchers.

Along with those findings of gender bias in peer review, overall data clearly show that AGU needs to engage more younger scientists and also more scientists from outside the "First World".. Thus, the peer review process is adversely affected in terms of an age bias (favoring older researchers) and also favoritism toward reviewers in more developed nations. The first is perhaps more understandable given people collectively tend to accept those who are older have more experience, so should be better at what they are tasked to do, including assessing the work of peers. Older reviewers are also more likely to be fully tenured professors, as opposed to assistant professors.

The second is harder to grasp but something I have run into, having completed my postgraduate work at a foreign university (University of the West Indies) rather than an American or European one. I suppose the applicable assumption involves the wrongheaded take which conflates the offshore medical school (say as found in a number of Caribbean nations) with all Third world foreign universities, i.e. being substandard. So, because some Caribbean medical schools may be below par the reasoning is that all Caribbean, African or Asian universities (in whatever field) must be as well. This is an example of the fallacy of composition, or assuming that because one part of an aggregate (say a Caribbean medical school) has an undesirable attribute, then all foreign universities must as well.

For me, the kibosh landed on this fallacy after my appointment as a peer reviewer by the National Science Foundation in the 80s - for space and solar physics papers. A major reason, of course, was on account of having a specialty in the area of statistical limitations related to solar flare and sunspot phenomena. (Including applications of the Poisson distribution to geo-effective flare frequency.)

For me, the kibosh landed on this fallacy after my appointment as a peer reviewer by the National Science Foundation in the 80s - for space and solar physics papers. A major reason, of course, was on account of having a specialty in the area of statistical limitations related to solar flare and sunspot phenomena. (Including applications of the Poisson distribution to geo-effective flare frequency.)

If the trope that foreign (e.g. 3rd world) universities are inferior were true it would also follow that those who graduate from these universities would not get published as often as their peers in the 1st world. This is demonstrably false when one examines the total constellation of published papers in all scientific fields - and compares the authorship based on proportion of population by national origin.

But the biggest immediate impediment to better peer review is the one governed by gender bias. Most compelling here is the April issue of AGU's largest journal, Geophysical Research Letters (GRL), wherein one read the following statement:

Evaluation of our journals’ peer review practices suggests that women were less likely than men to be asked to review. Please help us improve the diversity of our reviewer pool by including women, young scientists, and members of other underrepresented groups in your suggested reviewers (e.g., age, ethnic, and international diversity).

Other data show a marked increase in the acceptance of the invitation for women to review, especially by women scientists. This increase likely reflects a broader awareness of the gender bias issue prompted by the Nature paper, It is important to point out that such awareness was not likely to be found in physics, geoscience, and astrophysics papers even 40 years ago. This may be because too many women researchers - often in the assistant professor position - were rarely even considered as principal authors in a major paper. Hardly any principal authors meant even fewer reviewers.

Although the gender diversity of reviewers has improved, the data so far for 2017 indicate that the GRL statement has not so far led to a significant change in recruiting reviewers for that journal who are younger or who hail from countries outside North America and western Europe. So why the persistence of reverse ageism as well as cultural -national preference for reviewers? We can't be sure but it's most likely because the referee position is still dominated by a certain type (e.g. older white males) and these will only yield very grudgingly.

To their credit, AGU editors have been conducting workshops on reviewing, including recently at the International Geological Congress meeting in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Japan Geoscience Union–AGU meeting in Chiba, outside of Tokyo, and in visits to universities and research institutions in China. AGU Publications has also conducted several webinars on reviewing, including the most recent on “How to Write Effective Reviews (and Improve Your Own Manuscript),” and will expand these efforts further.

The AGU also plans to continue to collect and report data on reviewer diversity in its scientific publishing and provide regular updates. The payoff will ultimately be greater peer reviewer diversity - not only by gender- but also by age and national origin. This is bound to enable more diverse papers in all disciplines to see publication.

This does not mean the number of climate change "skeptic" or "iconoclast" (aka denier) papers will see more publication, unless and until they can adhere to the rigors of science. It might actually be better, since the deniers are really about economics, they seek to get published in that domain. They can then focus their mental energy on the economic reasons for resisting climate change and the need to reduce carbon emissions - which is what their specious science is really about.

No comments:

Post a Comment